ICE’s civilian recruitment and expanding detention echo the patterns of history—and offer a warning we can’t ignore.

Ordinary Men, Extraordinary Lessons

In 1992, historian Christopher Browning published Ordinary Men, the story of Reserve Police Battalion 101 - a group of about 500 middle-aged German men, most of them shopkeepers and truck drivers. Drafted into service during World War II, they were sent to occupied Poland, where they became participants in mass shootings and deportations of Jews.

Browning’s finding was unsettling. These were not fanatics. They were ordinary people who complied because it was easier, because their comrades did, because the tasks were broken into bureaucratic steps that felt routine rather than monstrous. A few refused and were reassigned. Most went along.

The Holocaust was genocide; U.S. immigration enforcement is not. But Browning’s study reveals how states expand power by recruiting ordinary people into extraordinary actions. The lesson is not equivalence, but warning: once the machinery of compliance is in place, it can be directed toward ends far beyond its initial justification.

Civilians Invited to Join ICE

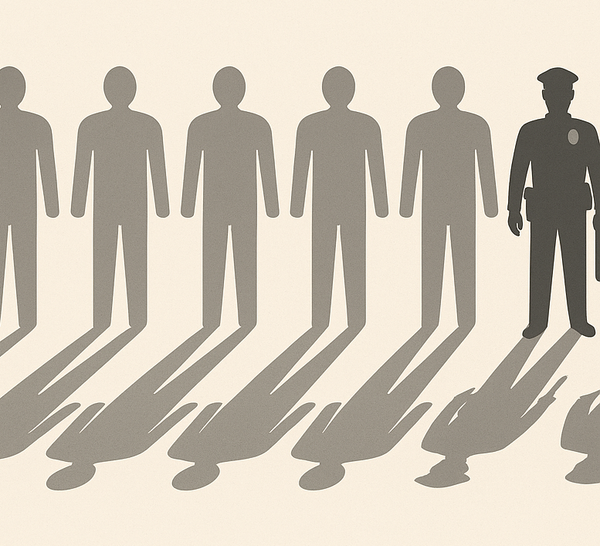

Earlier this year, the Pentagon quietly invited nearly a million civilian employees to volunteer for temporary assignments with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and Customs and Border Protection. On paper, the roles looked harmless: logistics, planning, support work. In practice, they represent something larger—a state expanding its capacity for detention and deportation by recruiting ordinary people into extraordinary tasks.

Browning would recognize the pattern immediately. What is different now is how freely many seem to join. Where his “ordinary men” complied reluctantly, today’s volunteers step forward willingly.

“Do not obey in advance. Most of the power of authoritarianism is freely given… A citizen who adapts in this way is teaching power what it can do.” - Timothy Snyder

Capacity First, Questions Later

The Army has awarded a $200 million contract to build a detention facility at Fort Bliss, Texas, capable of holding 5,000 people. The logic is bureaucratic: anticipate demand, build capacity. But capacity is never neutral. Once beds exist, pressure builds to fill them.

Reserve Battalion 101 began with deportations framed as logistics. Killings followed once capacity and routine were in place. America’s detention centers are not the same, but the sequence is familiar.

Dragnet Screening of Millions

More than 55 million visa holders are now subject to “continuous vetting.” Phones are inspected at interviews. Social media is combed for red flags. What was once background checking has become a permanent dragnet.

In the 1940s, paper ledgers sorted populations for deportation. Today, algorithms and cross-referenced databases do the same work, invisibly and at scale.

A Blueprint for Expansion

If these steps were happening in isolation, they might not be as concerning. But they align neatly with a political playbook already written. The Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025 lays out an aggressive vision for immigration enforcement. Among its recommendations:

- Make E-Verify mandatory for all employers.

- Condition federal funds on state cooperation with ICE detainers.

- Expand the 287(g) program that deputizes local police as immigration officers.

- Reinstate “Remain in Mexico” and fast-track asylum processes designed to limit hearings.

- Narrow or eliminate humanitarian parole.

- Change “may detain” to “shall detain” in statute, reducing discretion.

- Integrate U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services more deeply into national security databases.

This is how Browning’s ordinary men became perpetrators, not with one sweeping order, but through bureaucratic shifts that normalized harm.

The danger is not only deportation. Once such a machine exists, its logic can be redirected. What begins as immigration enforcement could easily be repurposed to target political opponents, activists, or other vulnerable groups.

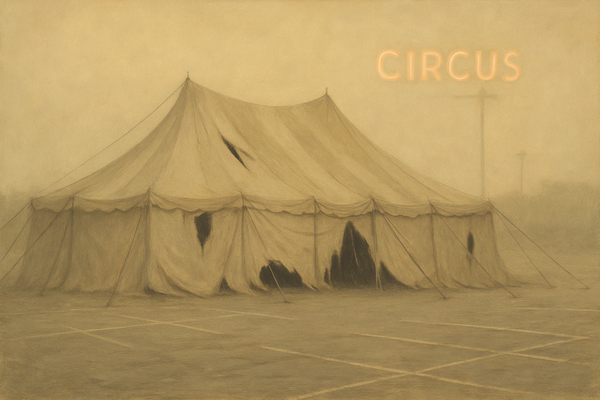

Language That Dulls Conscience

Browning noted how euphemisms softened violence: “resettlement” instead of shootings. Today we hear of “processing,” “austere conditions,” “soft-sided facilities.” Language does not kill, but it makes harm easier to accept.

Once a machine of detention is built, it rarely stops at the task it was created for.

A Democratic Warning

The United States is not Nazi Germany. Immigration enforcement is not genocide. But the mechanisms Browning identified—bureaucratization, deputization, euphemism, capacity building, diffusion of responsibility - are alive today.

And deportation may only be the beginning. ICE’s model - civilian auxiliaries, executive-controlled warrants, nationwide surveillance- could easily be redirected against political opponents or activists. Legal remedies come slowly, long after masked agents have taken people away.

Snyder reminds us:

“History permits us to be responsible: not for everything, but for something.”

That responsibility begins with noticing mechanisms as they form. Deportation is the case study. But the true danger is the machine itself, and what else it could be turned to do.

Share this article

Written by

Join the conversation

1984 Wasn’t a Warning, It Was a Blueprint

Ten Lessons From Orwell That America 2025 Is Failing to Learn War Is Peace. Freedom Is Slavery. Ignorance Is Strength. George Orwell’s slogans weren’t meant as prophecy. They were meant as diagnosis: how fragile truth becomes when power is unchecked. In 2025, the United States is watching an

When Democracy Fails: What the DNC Still Does Not Understand

On The Weekly Show with Jon Stewart, Democratic Party Chair Ken Martin was handed an opportunity: lay out what Democrats stand for heading into 2026. Instead, what viewers saw was the emptiness of consultant-speak and the absence of a vision.

Crowd-Sourcing Democracy: How the Exhausted Middle Can Rebuild Trust

American politics is unraveling inside our closest circles. Families and friendships that survived disagreements for decades are now breaking apart. What once felt like arguments about taxes or foreign policy are now fights about reality itself. The far right has become louder, comfortable speaking openly about racism, exclusion, and authoritarian